The State of Delivery Robotics in 2023

Assessing the competitive landscape, as Serve drives towards a public listing

Over the past few months, we’ve sat down with leadership from all of the major delivery robotics startups, gathering their insights and prognostications during an interesting inflection point for the industry. On one hand, tomorrow never comes as fast as predicted, especially if your prediction was used to raise a big venture round back in the halcyon days of early 2022. But at the same time, a number of players have made unmistakable progress – not only securing major partnerships “vote of confidence” partnerships, but with a number of companies now reporting profitability on a per-delivery basis.

With Serve, one of the industry’s larger players, making waves late last week with the news that it planned to go public, this felt like a natural time to sift through all of our interviews, and suss out a path forward for the entire personal delivery device (PDD) space. With the major players differing on key decisions like form factor, autonomy, monetization strategy, target customer and more — there are still a number of paths forward.

How deep is your tech?

The major inflection point the industry is still divided over is how deeply to invest in autonomy. While we’ve seen some startups falter at the extreme ends (fully autonomous Nuro slashed staff count and delayed its next hardware release, while completely remotely-operated startup Tortoise wound down,) the remaining contenders are all over the map in terms of how autonomously they operate.

In its SEC filings, Serve reported that its Level 4 autonomy is effective >80% of the time; competitor Starship claims 99% autonomous operations. Other players like Coco have stuck with remote-operations, whereas Kiwibot recently jumped from Level 3 to Level 4 automation. One question that’s dogged a number of companies as they try to move up the autonomy scale is just how efficient they are with their human pilots and drivers. Industry sources have reported that some “autonomous” players still essentially employ one remote driver / minder for every robot; that’s great news for suppliers like Remotics, but not good for bending the cost curve.

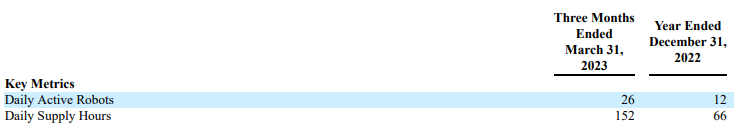

In theory, opting for more autonomy should mean more fixed costs as you pour money into R&D, but low variable costs, as each robot doesn’t require another corresponding human to work it. But the financials only really work out if you can keep your robots working around the clock. In its disclosures, Serve noted that while it grew its “daily active robot” count from 12 to 26 between 12/31/22 and 3/31/2023, its daily supply hours” only rose to 152 – meaning each PDD is ready to accept jobs 5.85 hours per day, implying even fewer hours are then spent on delivery runs.

Other tech issues still divide the field: how many gallons or grocery bags of storage should your robot hold; how heavy should it be; three wheels or four; why does Refraction’s vehicle look like someone stole The Terminator’s head? But ultimately each decision is driven by a combination of rationalizing costs, while trying to maximize each bot’s earning capacity.

Fundraising fun

Speaking of earning, money has obviously been on the minds of industry leadership. In 2021 and 2022, low interest rates and a COVID-induced boom in delivery meant Nuro could raise a whopping $2.1 billion dollars; Starship raised $100M in 30 days; Coco’s Series A was a mighty $36M. Heck - that all sounded reasonable in an era where companies were raising billions of dollars on the idea that they would cover the planet in dark warehouses so humans could deliver you candy bars in 15 minutes or less. (How’d that work out?)

These days, startups are learning to stretch their dollars, and finding they have to get creative when it comes to fundraising. Kiwibot turned to Kineo Finance to raise $10M in asset-based financing, essentially using the new bots it would build as collateral for the loan. Before announcing its turn towards the public markets, Serve went from a crowdfunding round to $3M in bridge financing.

But with both venture funding and the NASDAQ looking a bit healthier these past months, perhaps things are turning around for the industry. Or maybe, some players will manage to make it out without any more external capital. Starship recently announced it was profitable in select markets, and Cartken claimed it was in the black on a per delivery basis. Remotely operated players are making financial headway too. One familiar brand (that has asked not to be named) is also profitable on a per delivery basis. Reflecting on his company’s financials, Tiny Mile’s Ignacio Tartavull shared that his company was generating about $1M in revenue on $2M in burn, which works out to roughly 10x of Serve’s revenue on 1/10 the costs. With delivery behemoths like Uber and Delivery Hero now breaking even, perhaps we’ve finally reached a point where delivery can make money?

Which way are the policy winds blowing?

When we think about the policy and laws dictating robotic delivery operations, there are really two distinct subsets: where PDDs can operate, and how they can operate. That latter question has been left relatively unaddressed by both the public and private sector; we’re in the “primordial soup” phase, where each operator evolves its own answers to the questions of not just how the insides of the machine work, but how that machine communicates to the public, and what sort of reliability it must offer.

One organization, the Urban Robotics Foundation, is trying to standardize the industry, as it shephards ISO 4448 towards finalization. As sidewalk robots proliferate, it only makes sense that the public should expect predictable behavior when it comes to issues like yielding to wheelchair users, communicating intention to cross a street, waiting for other vehicles with right of way, etc. While the public might find robots crashing through caution tape amusing these days, that behavior won’t be tolerated at scale.

The Open Mobility Foundation also has its eyes on delivery robot regulation, as version 2.0 of its Mobility Data Specification now supports flexible data formats for tracking PDDs. Cities as varied as Bogotá, Los Angeles, Miami and Auckland use the framework to track and enforce micromobility usage; expect to see more and more cities use it to monitor delivery robots, and potentially set “no go” zones, in the near future. As of now, Kiwibot appears to be the only PDD company that’s an active OMF member, helping shape the software standard could give them a leg up in the long run.

Cities, especially in North America, have continued to take a broadly hands-off approach to regulating delivery robotics. There are some notable exceptions: Toronto passed a ban in late 2021, sending Tiny Mile’s robots (but not all of its leadership) down to Miami. San Francisco banned the bots way back in 2017, back when Marble was considered a serious competitor. While sidewalk bots are currently not allowed on public streets in Las Vegas, a legal update may soon change that.

Going to market off going to the market

On the other hand, Los Angeles, along with neighboring Santa Monica, has continued to offer a relatively hands-off approach to the industry, letting a number of players comply with its 2021 guidelines (PDF.) This has made for a sea of machines crossing the street in certain neighborhoods, reminiscent of the scooter glory days of 2019. Serve has made itself particularly at home in Hollywood, while Coco sticks to the beach near its HQ, and Kiwibot plus competitors dot other neighborhoods. In keeping with its campus-first strategy, Starship serves UCLA, a good way to ensure fewer conflicts with traffic and the wild variables of city streets.

These startups have taken a broad approach to how they work with both merchants and end consumers. Starship generally has users order directly from its own app, building a relationship and securing a nice $2.49 fee; but on some campuses orders are handled via Grubhub. That same 3PD has been playing footsie with a number of startups, also inking deals with Cartken and Kiwibot, in the wake of its earlier partnership with Yandex exploding like a Ukrainian drone hitting a Russian bridge. Uber sticks closer to Serve, as it still maintains a 16.2% stake in the company, which was originally built as a Postmates skunkworks project. DoorDash has been far less active in the space, quietly tinkering with Starship and full-size AV player Cruise, and more recently filing a few patents of its own. Operators like Refraction have opted to work directly with restaurateurs, scoring notable contracts with the likes of Chick-fil-A; others like Tiny Mile instead let customers opt in to dispatching the bots themselves, monetizing via on-robot advertising. (Will those ad rates stay steady once the novelty dissipates? The struggles of other ad-supported mobility startups like Volta and Swiftmile suggest a tricky road ahead.)

One thing the competitors can seem to agree on is that fresh food is a better use case than groceries, for a combination of size, weight, and consumer speed expectation reasons. Starship ended its grocery partnership with NorCal-based Save Mart; Tortoise couldn’t cross the road from Safeway or Walmart to your pantry, it pivoted to mobile-vending before folding. While Europe’s Delivers.AI promises to enter the U.S. market via a partnership with Atlanta’s Nourish + Bloom, the fact that they’ve chosen a grocer with one live location shows just how far this use case has fallen. Even for the delivery robots going after very specialized use cases, like Ottonomy’s fixation on airports, the cargo tends to be lunch or dinner.

Serve heading towards the public markets is a momentous moment for the delivery robotics industry. While the company generated $107,819 in revenue last year, it did so while losing $21,855,127, meaning it will need to hit the gas on growth, or do an at the market offering, to deliver on its ambitions. But with a number of competitors still hungry to win, the future looks promising for sidewalk bots.

State of play for PDD competitors

For in-depth profiles on each delivery robotics company, read our recent conversations with their executives.

Cartken

Cartken’s been a quiet player in the space, with a team that spans Germany and NorCal, although some execs have recently relocated to Southern California. The company, which works with Grubhub, claims profitability on a per-delivery basis.

Exploring the Future of Delivery Bots with Cartken's Christian Bersch

Cartken has racked up some impressive wins in the PDD / delivery robotics space, including partnerships with Grubhub, unique deployments in the hospitality space, and more. Despite this, the company seems to fly a bit beneath the radar - attracting less attention than the likes of Coco, Kiwi and Serve. To help fill in the blanks, we sat down with company CEO

Coco

Originally known as Cyan Robotics, Coco’s Zach CEO Zach Rash co-founded the company based on his research at UCLA. While the startup has since dabbled in Texas, the bulk of its operations remain at home in West LA, where it works with restaurateurs that include poke purveyor Sweetfin.

Coco’s Zach Rash on Delivery Density, Profitability and Regulation

As OttOmate continues to sit down with the leaders of the delivery robotics revolution, this week we’re delighted to chat with Coco’s CEO and Co-Founder Zach Rash. With an engineering background from UCLA, Zach and his team have spent a lot of time thinking about the ideal hardware and operating environments for PDDs. Industry watchers may want to note how the company’s lessons learned in parts of Texas (too sprawling to support the service) may apply to other Southeastern markets.

Delivers.AI

Delivers.AI strolls the streets of Turkey and England, where it’s pushed out partnerships with the likes of 3PD Glovo and autonomous vehicle aggregator Goggo. It hopes to push into the U.S. market later this year, via a partnership with tech-focused independent grocer Nourish + Bloom

Nourish + Bloom: Georgia's High-Tech Grocer

When it opened in January 2022, Nourish + Bloom garnered praise from across the country, as shoppers and reporters flocked from far and wide to check out the first Black-owned, autonomous grocery store. Now nearly a year and a half into operations, OttOmate

Kiwibot

While Kiwibot’s leadership spans California, Florida and Bogotá, its robots’ remote operators are solidly based in LatAm. The company has deals with Grubhub, Sodexo and financier Kineo Finance.

David Rodriguez's "High-Driving" Delivery Bots Are Here to Stay

As one of the earlier startups to enter the autonomous sidewalk delivery space, Kiwibot knows a thing or two about zigging and zagging. That lets the company’s eye-catching hardware maneuver around obstacles, and also allows the team to respond to market conditions with

Motional

Backed by Hyundai and Apriv, Motional’s full sized AVs are moving meals for Uber Eats, which also has a deal with Waymo. While other non-sidewalk sized players, like Nuro and Cruise, have backed away from the space, Motional sees it as a way to balance fleet usage.

Motional Sees AV Deliveries Balancing Robotaxi Service

As we catch up with the leaders in the autonomous delivery space, it’s worth noting that our conversations thus far have all been with folks working at the sidewalk scale. For a sense of comparison, let’s check in with Motional, the AV upstart backed by Hyundai and Aptiv that’s

Ottonomy

The less you can navigate busy city streets, the better. While Starship (and sometimes Kiwibot) have taken that maxim to mean they should serve colleges, Ottonomy has instead largely opted for the confines of airports.

On Airport Delivery & Investor Revenue Demands

2023 has been an exciting year for Ottonomy, an autonomous delivery startup that’s nominally based in the U.S., but houses almost the entirety of its team in India. First it signed a distribution agreement with European logistics operator Goggo Network

Refraction AI

With leadership in both Austin and Ann Arbor, Refraction AI has signed partnerships with some of Middle America’s favorite brands, including Chick-fil-A. The startup has taken a differentiated approach to hardware design; an updated version may be on its way.

Refraction AI's Luke Schneider Is Going the Distance

It’s been almost two months since we checked in with an exec leading the charge at a delivery robotics startup, but our latest installment is well worth the wait. Luke Schneider, who serves as CEO of Refraction AI, heads a company that’s been a tad more coy with the press than some of its industry peers. He’d rather be hard at work in the background, scoring major partnerships with the likes of

Serve Robotics

Spun out of Postmates after the 3PD was acquired by Uber, Serve has gone deep in the LA market. It now looks to be the first PDD company to hit the public markets.

Serve's Aduke Thelwell Discusses Equity Crowdfunding Campaign

Serve Robotics has been making a lot of waves as of late, including a team-up with 7-Eleven to handle 7NOW deliveries in Los Angeles. But the company’s recently announced equity crowdfunding campaign has been generating even more buzz in industry circles. I sat down (virtually) with Serve’s Chief Communications Officer Aduke Thelwell, to get additional insights on the fundraising.

Starship Technologies

Created by Estonia’s favorite technologists, ex-Skypers Janus Friis and Ahti Heinla, Starship was founded in 2014, before launching a pilot two years later. While the company plies many a U.S. college campus via a partnership with Sodexo, its bots can also be found on city streets in places like Milton Keynes, England. The company’s robots have driven over five million miles, and the firm is profitable in select geographies.

Starship’s Henry Harris-Burland: 'We Are Now Cheaper Than Human Delivery'

As OttOmate continues to sit down with the best and brightest minds in the robotic delivery industry, we’ve worked our way over to industry juggernaut Starship Technologies. Founded way back in 2014, its arguable that the entire sector would not exist if not for Starship’s pioneering work in both consumer acceptance and legislative positioning. Henry Harris-Burland, the company’s VP of Marketing, gives us the company’s latest impressive milestones.

Tiny Mile

After Toronto nixed PDD operations, Tiny Mile moved its robots to Miami, followed by an expansion into Charlotte. Ever economizing, the company shaved its bots down to three wheels, and monetizes its user-dispatched machines with advertising.

Tiny Mile Zigs Where Other Delivery Bots Zag

Whereas many in the delivery robotics industry have set their sights on restaurant and grocery delivery, the team at Tiny Mile has taken a different approach: their petite pink robots act as couriers, open to the public at large. Instead of charging consumers or merchants for this service, Tiny Mile offers it a must-try $0 price point, with the service entirely underwritten by advertising. That’s kept the company super-disciplined on keeping costs low, as evinced by the somewhat workman-like design of its robot, aptly named Geoffrey. And despite making headlines for being kicked out of

Tortoise

Before co-founding Tortoise, Dmitry Shevelenko racked up industry experience at the likes of Uber and Superpedestrian. The company took its teleoperated tech, originally designed for micromobility, into the robotics space, as it delivered for Walmart and Safeway, before pivoting to mobile vending machines. With the company now dormant, its leadership warns other startups to avoid “getting stuck in the middle.”

Tortoise’s Dmitry Shevelenko: Consumers Thought They Could Buy Something From the Robot

With the autonomous delivery industry in a momentous state of transition, I’m sitting down with execs from the leading PDD players to gather their insights into the challenges facing the sector. Summing up their thoughts on fundraising, sales, regulation, and more - we’re already starting to see some interesting trends emerge. (See these recent interviews with Cartken’s

Yandex & Europe

All’s quiet on the European front! Russia-based Yandex has kept mum since losing its major partnership with Grubhub last year. While the company’s Self Driving Group has continued to progress its robotaxi operations in Moscow, its food delivery arm has gone silent. Fellow European Teraki has also been relatively quiet, making few announcements since it concluded a five week pilot with Domino’s and an unnamed hardware partner in mid-2022. Also staying under the radar as of late are Yape and Piaggio’s Gita.

Grubub Yanks Yandex Robots From College Campuses

Last week, we asked whether Grubhub would continue using delivery robots from the Russian tech giant Yandex. While they never replied to our inquiries, the NY Post got the skinny last Friday that Grubhub has in fact stopped using Yandex’s robots. This means that students at Ohio State University in Columbus, Ohio, and the University of Arizona in Tucson, Arizona no longer have access to robot delivery of meals and snacks.